I'm an early-retiree who doesn't index. It's a choice that I've made with a clear understanding that, when investing in the stock market, doing so via indexing is now the overwhelming preference and recommendation of those in the early retirement community (and beyond). Instead of indexing, I choose to invest for dividends - via a portfolio comprised of a relatively small number of stocks. Stupid? Foolish? Misguided? Maybe. Maybe. Maybe.

Or, it might be that, for the purposes of early retirement, investing for dividends is a very viable investing option. To be clear, I'm not trying to discredit index investing. I think it's a great option. But, I also humbly assert that dividend investing is an equally great option. Here, I put forward my case for you to decide.

I've been retired for a couple years now, since I was 43. For the most part, I live off of dividends paid out by the individual stocks I hold in a taxable brokerage account. In other words, I don't sell stocks to provide income or cover any of my living expenses.

Dividend Basics

Before proceeding, let's make sure we all understand what dividends are and how they work.

"A dividend is a payment made by a corporation to its shareholders, with each share receiving an equal amount of value. ...the vast majority of dividends are regular cash dividends, paid at predictable intervals—usually once every three months in the United States."

~ The Morningstar Guide to Dividend Investing

Simply by virtue of owning one or more shares of a stock that pays a dividend, you'll receive cash dividend payments (on a regular basis) into the account where you hold that stock. The size of those payments is determined by the stock's annual dividend rate. Because stocks are denominated in shares, the annual dividend rate is expressed as a per-share amount, paid annually. For example, if Company, Inc. pays an annual dividend rate of $3.23/share and you own 50 shares of Company, Inc., you will receive a total of $161.50 in dividend payments over the course of a year.

$3.23 * 50 = $161.50

If Company, Inc. pays out dividends on a quarterly basis (which is common in the United States), you will receive ~$40.37 every three months.

$161.50 / 4 = $40.375

Just as the share price of different stocks will vary a great amount, the annual dividend rate of different stocks will vary just as much. As such, a typical metric for quantifying and comparing the dividends of various stocks is the dividend yield. A stock's dividend yield is calculated by dividing the stock's annual dividend rate by the stock’s current share price. For example, if Company, Inc. trades at $85/share and the dividend rate for Company, Inc. is $3.23/share, the dividend yield of Company, Inc. is 3.8%.

$3.23 / 85 = 3.8%

Outside of dividends, an investment yield you may be more familiar with is the yield on a bank savings account.

Why Dividends

I hold dividend-paying stocks because I find them to be my best all-around option for earning passive income from my savings. It's the option that best suits my preferences. This is in contrast to the prevailing opinion in the FIRE community that favors total market index-based mutual funds and ETFs (typically those offered by Vanguard). In fact, most of the FIRE luminaries I actively follow and respect go with index investing. And yet, I don't. I'll explain why.

The income I earn from dividend-paying stocks is

- substantial

- stable and consistent

- inflation-resistant

- tax-advantaged

- easily-harvested

- low-stress

Substantial Income

The current dividend yield on Vanguard Total Stock Market ETF (VTI) is 1.81% and the dividend yield on Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund (VTSAX) is 1.83%. In comparison, the dividend yield I realized last year on my taxable stock holdings was in the neighborhood of 4.4% (depending on how you calculate it). According to my brokerage, my estimated dividend yield for the coming 1 year period is 4.3%. That's a juicy increase in income compared to what is probably the two most popular total market indexing options - more than double.

Please note that I'm just comparing income here, not total returns or capital gains. I'll touch on total returns later.

Stable and Consistent Income

Just as many/most people enjoy (or seek out) the stability provided by receiving a predictable paycheck every week or two, investors can find the same sort of stability from stocks that pay dividends.

Stock prices yoyo up and down constantly. Relative to the underlying stock prices, dividend rates tend to be very stable and tend to rise steadily (although dividend rate cuts do definitely happen). As a result, while the per-share price of a stock may spike up and down over the course of a year, the odds are good that the dividend payments made to you by that stock will remain stable, from quarter to quarter and from year to year.

Dividend-paying companies announce and maintain schedules for when they will make future dividend payments. Most dividend-paying US companies follow a schedule of paying out dividends every quarter, meaning one of the following schedules:

- January, April, July, October

- February, May, August, November

- March, June, September, December

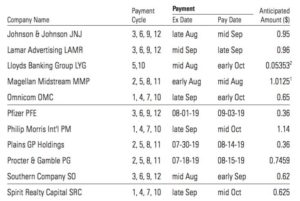

It's rather rare for a company to deviate from an already-announced dividend payment schedule. As such, you can actually mark on your calendar when you can expect to be paid. Given enough individual stocks held, you'll end up receiving dividend payments from multiple stocks over the course of each month.

Inflation-resistant Income

A worthwhile dividend-paying stock (or, rather, the underlying company) grows at a rate that is, to some degree, greater than inflation. This growth, over a long time frame, tends to derive from an economic moat. It's this moat which serves to insulate company profits and market share. For those "moaty" companies, the dividend rate tends to rise in a similar fashion (faster than inflation). This is simply by virtue of the company deciding to remain committed to their dividend. If a company with a rising stock price does not raise their dividend rate in a similar fashion, their dividend yield will decrease and they will incur the risk of investors taking their investment dollars elsewhere.

In short, just as a worthwhile dividend-paying company tends to be inflation-resistant, so does its dividend. However, just as the performance and fundamentals of a company can strengthen and weaken, so can the growth rate of its dividend.

Tax-advantaged Income

The tax rate for qualified dividends is 0% for single filers with taxable income up to (currently) $38,600. For married filers, that threshold is (currently) $77,200. Most "bread and butter" dividend-paying stocks pay such qualified dividends (as opposed to non-qualified dividends). By all appearances, most early retirees in the FIRE community owe their early retirement to lifestyles that feature low expenses and correspondingly low post-retirement incomes. (At a minimum, that sums up my case.) As such, these taxable income thresholds are well within reach.

This treatment by the tax code puts income derived from dividends on par with income derived from long-term capital gains (which is the sort of income you'd realize from indexing).

Even better, if you decide to invest in MLP (Master Limited Partnership) stocks, MLP income is tax-free, regardless of income level. However, it is very common for index-based mutual funds and ETFs to avoid holding MLPs. Given the complexities of owning MLP stocks, which I'm not going to dive into here, this is understandable. And you, as a potential dividend investor, may very well decide to exclude them, too.

Easily-harvested Income

When you invest for dividends, you can live off of yield only. You don't need to touch any principal. In other words, you don't need to sell shares to provide yourself regular recurring income. It's like opting to have your paycheck direct-deposited. The only additional step you need to do is to transfer those dividend payments from your brokerage account to your checking account every month or so. Very easy!

In contrast, when indexing, you need to sell a small portion of your ETF or mutual fund holding(s) on a regular basis. That's not necessarily hard, but something is harder than nothing.

Low-stress Income - Withdrawal Rate

"The 4% rule is a rule of thumb used to determine how much a retiree should withdraw from a retirement account each year. This rule seeks to provide a steady income stream to the retiree while also maintaining an account balance that keeps income flowing through retirement. Experts consider the 4% withdrawal rate to be safe, as the withdrawals will consist primarily of interest and dividends."

~ Investopedia

Like many, I believe in the veracity of the 4% rule - and I strive to abide by it. But the 4% rule was devised for traditional retirees - those retiring at age 65 and living another 30 years. For early retirees, retirement will, hopefully, last much longer. And so those savings need to last much longer.

On that point, well-respected figureheads within the FIRE community such as Mr. Money Mustache, Go Curry Cracker, The Mad Fientist, and J. L. Collins argue that the 4% rule applies equally well to retirements lasting longer than 30 years. This is based on a mix of a) taking a look at the raw study data and b) placing faith in the ability of early retirees to adapt in the face of (presumably short-term) adversity.

If you share their confidence, then stress isn't an issue for you. So, you could consider this point moot.

Personally, instead of focusing on the raw 4% portion of the rule, I prefer to focus on the part about how "...withdrawals will consist primarily of interest and dividends".

When investing for dividends, you can punch your yield up above 4%. If your expenses are low enough that you can live off of the resultant dividend payments alone, you are abiding by the 4% rule on income alone. In contrast, if the index investor's principal is the same, but their yield is lower, they will need to sell shares to account for the balance of their withdrawals. Is this a big deal? After all, 4% is 4%, right? Hmm - maybe not.

When selling, the fluctuating valuation of the index investor's portfolio is a variable that can become a liability. If the market loses 25% of its value for 1 year, what previously amounted to a 4% withdrawal rate becomes 5.3% for that year. If the market loses 50% of its value for 1 year, what previously amounted to a 4% withdrawal rate becomes 8% for that year.

If you are an early retiree who is trying to apply the 4% rule to a 40- or 50-year retirement, in those down-market periods, it would be a good idea to withdraw a smaller amount (whatever equals 4%) from your retirement account and figure out a way to live on that smaller amount. This is the adaptability that Mr. Money Mustache, Go Curry Cracker, etc. espouse in the applicability of the 4% rule to early retirement. But, keep in mind that this expense reduction is warranted because a large portion of the index investor's withdrawals are comprised of principal.

Contrast this with a dividend-focused portfolio yielding 4%. On the surface, the numbers stay the same. A 25% market downturn turns a 4% withdrawal rate into 5.3%. A 50% market downturn turns a 4% withdrawal rate into 8%. And yet, because the early-retiree dividend investor is living on the income provided by that 4% yield, alone, there's no reason to withdraw a smaller amount. While the withdrawal rates for both investors are technically the same, the impacts are much different. If the index investor does not decrease their withdrawals, they will eat away an out-sized portion of their principal, For the dividend investor, that worry isn't there because the principal isn't being touched.

A dividend investor living on yield alone has (almost?) no reason to worry about out-living their money, regardless of time span.

To compensate for the possibility outlined above, the early-retiree index investor may choose to increase their amount of principal so that their 1.8% yield (the current yield of VTI and VTSAX) brings in more income. However, pursuing this will cause them to push back their financial independence and/or early retirement date. But, again, this is only if the index investor lacks the confidence demonstrated by the likes of Mr. Money Mustache, Go Curry Cracker, etc.

Low-stress Income - Seamless Transition

As I was approaching early retirement, I spent a lot of time trying to identify all of the "seams" between pre-retirement and post-retirement that I'd be liable to trip over. Each one of those seams was some sort of difference or "unknown" that could threaten the success of my retirement. As such, I wanted my transition from pre-retirement to post-retirement to be as seamless as possible. In that regard, being a dividend investor proved to be very valuable.

Assume a dividend investor. Pre-retirement, dividend payments flow into their investment account on a continual basis (along with savings leftover from paychecks). That money will sit there for some period of time before it is eventually (re)invested in the market. Assume that dividend investor retires (and is able to live on yield, alone). Post-retirement, dividend payments continue to flow into their investment account on a continual basis, just as before. However, now the retiree withdraws that income to a checking account instead of (re)investing it.

That's a wonderfully seamless transition!

Now assume an index investor. Pre-retirement, savings leftover from paychecks flow into their investment account on a continual basis (along with dividend payments). That money will sit there for some period of time before it is eventually (re)invested in the market. Assume that index investor retires. Post-retirement, the retiree now needs to start doing something completely new and different - sell. They now need to start selling shares in order to realize income. This is unknown territory.

Over the course of years, possibly decades, the index investor has been averaging into the market. And that has worked to their advantage. They've been buying for so long that they have become completely comfortable doing it. But now, for the first time in their life, at a time of great change and uncertainty, they now need to start doing the opposite.

The averaging-in that has brought them so much comfort for so long now must be reversed.

"...when it comes time to take income you are put in the position of needing to sell off shares. This works as a form of reverse dollar cost averaging, since you are now selling into a changing market, rather than buying into it. That is, you will often be selling stocks at declining prices, and locking in your losses permanently."

~ Josh Peters

That's not a seamless transition at all. On the contrary, that's a disruptive transition. And it sounds like a pretty stressful one to me. You wouldn't expect Tom Brady to change the routine and habits that he has been following all season, right before the Super Bowl. As such, why would you?

Investing for dividends provides for a low-stress source of income in retirement. This can be contrasted with the stress encountered by an index investor when in retirement, brought about by concerns driven by market sensitivity. Speaking for myself, the closer I got to FIRE, the more I stopped keeping track of how my portfolio was performing compared to the market as a whole. All I care about now in retirement is my yield and annual income. Absent a market collapse and a slew of dividend cuts, market valuation just doesn't matter much to me.

Choosing Stocks

I hold individual stocks. The stocks I hold pay dividends that are (relatively) large, growing, and stable. I hold individual stocks because dividend-focused ETFs and mutual funds don't compare well - in terms of large, growing, stable dividends and minimal fees. I know of two worth considering:

- Vanguard High Dividend Yield ETF (VYM), dividend yield 3.11%

- Schwab US Dividend Equity ETF (SCHD), dividend yield 3.03%

However, their dividend yields are ~1% less than the yield I've managed to enjoy for a while now. If you've got a $1M investment portfolio, that's a difference of $10,000 less each year.

I do not pick my owns stocks. Instead, I mirror the holdings of the real-money Morningstar DividendInvestor (MDI) Dividend Select Portfolio. I've been subscribing to the newsletter that provides access to this portfolio since December 2007 or so.

I don't know enough (or care to know enough) about analyzing company financials to properly gauge the quality of a stock's dividend - in terms of its sustainability and growth prospects. So, instead, I pay for that expertise. MDI costs $199/year for a digital subscription. Is it worth it? Well, here's my thinking.

Let's assume a 1.8% dividend yield for a total market index ETF and a 4.4% dividend yield for a portfolio that mirrors the MDI Dividend Select Portfolio. If you assume $1M in investable assets, you would stand to make an additional $26,000 in annual income. To me, that is worth $199/year.

The MDI Dividend Select Portfolio currently holds ~30 stocks, which is typical for the portfolio. This number sits near the midpoint of the range (8 - low, 49 - high) of the number of stocks that studies have shown are required for a well-diversified portfolio. Even if the MDI portfolio wanted to hold a larger number of different stocks, it might not be able to. The truth is, there are a relatively small number of dividend-paying stocks that meet the portfolio's criteria.

MLPs and REITs

MDI does not shy away from including MLPs (Master Limited Partnerships) and REITs (Real Estate Investment Trusts) in their portfolio(s). In contrast, these holdings are frequently eschewed by most/all total market index ETFs and funds. (Sort of calls into question their characterization as "total market" offerings.)

If MLPs are an unknown concept, it could be due to the fact that the S&P 500 methodology specifically excludes MLPs. It could also be due to MLPs being ill-suited for tax-deferred investment accounts. To account for this, MDI maintains two real-money portfolios, with the first including MLPs and the second excluding MLPs. As such, the second portfolio can be mirrored for tax-deferred accounts.

The tax-deferred MDI portfolio variant (that excludes MLPs) currently sacrifices only .10% of yield in comparison to the unsheltered portfolio variant (that includes MLPs). I have always chosen to include MLPs in my portfolio. But, to be honest, looking at the minimal bump up in yield they provide makes me question that choice.

MLP income is tax-free for as long as the MLP is held. However, the cost basis of an MLP holding diminishes over time as the MLP is held, which could very well make for higher capital gains taxes if/when the MLP is eventually sold.

With regard to REITs, the dividend yields sported by REITs tend to be higher than those of non-REITs. However, REITs pay ordinary (non-qualified) dividends, which are taxed differently than the qualified dividends paid by most (non-REIT) companies. Ordinary dividends are taxed at ordinary income tax rates, regardless of tax bracket or taxable income. (Recall that the tax rate for qualified dividends is 0% for those whose taxable income remains below very-achievable thresholds.)

Arguments Against

There are several arguments to be made against dividend investing (in general) and the specific dividend investing strategy I've explained here (which is based on mirroring an MDI model portfolio). Those arguments are based on several concerns, including

- fragile dividend policies

- subscription/trading costs

- tax burdens

- portfolio manager vulnerability

- hands-on management requirement

- excessive capital gains

- anti-dividend philosophical bias

Fragile Dividend Policies

Dividends can be (and are) "cut". When a dividend is "cut", it means that the dividend-paying company has decided to reduce their dividend rate. So, in our earlier example of an annual dividend rate of $3.23/share, a cut could result in a new rate anywhere between $3.23/share and $0/share. With that being said, dividend cuts don't tend to be small. Such a cut would lead to an immediate reduction of income. Depending on how large a percentage one company's dividend contributes to your annual income, the resultant pain could be significant.

Companies can modify their dividend rates and payment schedules at whim. However, a worthwhile dividend-paying stock doesn't take the prospect of cutting their dividend lightly, as doing so incurs the risk of investors taking their investment dollars elsewhere.

Make no mistake, though - cuts do happen.

Subscription/Trading Costs

This concern is specific to my strategy. MDI costs $199/year for a digital subscription. The significance of that cost/fee depends on your portfolio. If you have a $1M investment portfolio, $199 is less than 0.02% of it. On the other hand, if you have a $50K investment portfolio, $199 is nearly 0.4%. In light of this, you may want to opt for index investing early in your investment career, then transition over to dividend investing (if done in a manner similar to mine) as your investable assets swell down the road.

It used to be that transaction costs warranted a mention here. After all, MDI executes one to two dozen transactions each year. If you assumed @6.95/transaction, that came out to be $166.80/year. However, with seemingly every brokerage adopting commission-free stock trades recently, this is no longer a concern.

Tax Burdens

Qualified dividends are (currently) taxed at the same rate as long-term capital gains. In retirement, given a low-enough taxable income, that rate will be 0%. However, prior to retirement, your taxable income will most likely be high enough that you'll have to pay 15% (of those dividends and gains) to taxes. (All of this assumes that the dividends are held in a taxable account.)

In light of this, conventional wisdom advises you to hold dividend-paying stocks in tax-deferred accounts. This is also one of the motivations critics cite for avoiding dividend-investing in favor of index investing. With index investing, income is principally realized by selling shares, and the investor chooses when to do the selling. With dividend-investing, the income is somewhat forced on you, along with the associated tax implications.

However, for early retirees, where the accumulation/preparation phase is shorter than the execution phase, I suggest focusing on minimizing the taxes paid during the longer phase, not the shorter phase. In this regard, dividend-derived income is on par with income derived from long-term capital gains.

But, I get the concern. After all, the length of everyone's accumulation/preparation phase varies. As such, you wouldn't be crazy to opt for index-investing early in your investment career, then to transition over to dividend investing as the plausibility of retirement draws nearer.

Beyond qualified dividends, REITs pay out ordinary (non-qualified) dividends. Whether you are in retirement or not, and regardless of your taxable income, ordinary dividends are not tax-free, ever. Ordinary dividends are taxed as ordinary income.

When you focus on investing for dividends, this is likely to become an exposure, as REITs are a prime source of dividend income. This is not to imply that an index investor is free from this exposure, as most/many index options will accrue some amount of ordinary dividends, as well. But, as the percentage of your income that is derived from ordinary dividends increases, your exposure increases. And it's fair to say that the typical dividend investor will earn more income via ordinary dividends than the typical index investor.

If this is a significant concern for you, you could choose to simply not invest in stocks that pay out ordinary dividends. But, a more nuanced response would be to do a cost/benefit analysis with each stock, comparing the increased dividend yield offered by each individual REIT stock to the increased tax that would be owed on the dividend income received.

One final item worth mentioning in relation to tax burdens centers on MLPs. While the income provided by MLPs is tax-free, owning MLP units (not shares) incurs complications when it comes to filing your annual tax returns. If this is a significant concern for you, you could choose to simply not invest in MLPs.

Portfolio Manager Vulnerability

This concern is specific to my strategy. It's also the principal concern I have with my strategy. In short, the strength of the MDI model portfolio I mirror is subject to the quality of the portfolio manager in charge of it.

The MDI model portfolio has had three managers since inception (January 2005). I would characterize that amount of turnover as modest. Among those three managers, I have my own personal order of preference. But, all have done, at minimum, a serviceable job. The possibility (and probability) of future changes does worry me, though. In this regard, I am putting myself at the mercy of Morningstar to do a good job of staffing the role.

Truth be told, investing for dividends in the manner I'm presenting amounts to stock-picking. Among most/all index investors, stock-picking is a dirty term. The thought that anyone can cherry-pick stocks that will "beat the market" over the long term is foolish and/or arrogant. By and large, I agree with this sentiment. However, this isn't stock-picking in the traditional sense of the term.

I'm looking for the portfolio manager to pick stocks that fulfill a specific set of dividend-centric criteria based on analysis of their fundamentals. I'm not looking for the portfolio manager to pick stocks whose share price will "beat the market".

Hands-on Management Requirement

This strategy requires more hands-on management than index investing. You must follow along with the buys and sells made in the model portfolio and execute your own trades, in turn. As such, this is not a "set it and forget it" strategy. Personally, I enjoy that level of ownership and involvement. You may not.

Excessive Capital Gains

The MDI model portfolio I mirror does not have a mandate to minimize taxes owed. Once you reach retirement, this can cause a bit of hand wringing.

Now that I'm retired, I'm always working to keep my taxable income below the threshold that allows for tax-free qualified dividends (and long-term capital gains). But, given a large-enough investment portfolio, it doesn't take many profitable stock sales in any one year to blow past that threshold. (And I'm not even going to try to go into the Affordable Care Act subsidy cliff.)

An inordinate amount of capital gains can significantly inflate your tax owed in any one year, especially if you don't have any losses carried-over from previous years to offset those gains. If those gains are earned in a year where your portfolio has significantly increased in value, it's hard to complain too much. You can just look at it as the "cost" of making money and "locking in" gains. After all, you're not going to go broke owing a single-digit percentage of a 30% gain.

However, it's possible that those gains could come in a down-market, in a year when your portfolio loses value. (Maybe a new portfolio manager took charge and decided to shape the portfolio more to their liking. This is just a simple example I can imagine.)

To be clear, when you are selling shares in order to produce income, it's understandable that that activity may generate capital gains. But the scenario I'm speaking to here is where one or more stock positions are reduced or sold (at a profit), simply for the purpose of optimizing/improving the make-up of the portfolio, theoretically for solid reasons. This is not an issue an index investor will typically face. Index ETFs and mutual funds typically track stable indexes - which do not result in a significant number of sell transactions and, therefore, capital gains.

Anti-dividend Philosophical Bias

The balance of arguments against investing for dividends amounts to a bias against dividends or a preference for indexing. I imagine that the credence you place in these criticisms will depend largely on which side of the divide you fall. But, I gain nothing by making "converts", so here goes. (If you want to read more details on these, take a look at the Mr. Money Mustache forum thread I sourced many of them from.)

Won't Beat the Market

"Investing for dividends won't beat the market." This argument comes up a lot. And I agree. But, the thing is, I'm not trying to beat the market. My goal is to maximize my passive income while staying within spitting distance (a low single-digit percentage) of the market. Investing for dividends does that for me.

Total Returns

"Index investing offers the best total return." This is mostly just an alternate phrasing of the "won't beat the market" argument. And, again, I agree. But, again, my goal is to maximize my passive income while yielding a "good enough" total return. As an analogy, consider car-buying. Just because Toyotas aren't the most reliable car brand doesn't mean that, for many people, they aren't "reliable enough". Whether or not you are one of those people is up to you.

Less Diversification

"Dividend investing leads to less diversification." I agree. But, how much diversification do you need? In my opinion, a healthy-enough level of diversification does not require owning "everything". If you have a differing opinion, that's fine.

Value Investing

"Dividend investing is value investing in disguise and you are better served to just invest in value stocks." Maybe, maybe not. I think it depends on your goal - maximizing your total return vs. maximizing your income. If your goal is the former, then maybe value stocks are your better play.

Survivorship Bias

"Investing for dividends is subject to survivorship bias." I may not completely understand this argument. If I do understand it properly, I would argue that every investment strategy that doesn't include everything is subject to survivorship bias. If you feel compelled to have your investment portfolio include everything (including stocks, bonds, precious metals, real estate, commodities, etc.), that's your prerogative. Go for it.

Better Use of Profits

"Company profits are better applied to internal initiatives or acquisitions." Maybe, maybe not. This is only true if management makes good choices. Personally, I believe that paying out a healthy portion of profits as dividends forces a healthy dose of financial discipline. Otherwise, those profits are likely to be squandered.

Forced Income

"Share buybacks are better than dividends, because the investor can choose when to recognize the income." I'd place more weight on this argument if dividend payments weren't made according to a pre-announced schedule. But, they are - which means you can plan for the income. But, to each their own.

Tax-inefficient

"Compared to dividends, buybacks are a more tax efficient vehicle for returning capital to shareholders." Agreed. When paying dividends, a company has to pay corporate tax on the earnings that ultimately fund those dividends before it can pay them out. And then the recipients are taxed on those dividends, again. That sucks.

Sign of a Bad Company

"A company that can't figure out anything better to do with their excess profits than to hand it out to shareholders isn't a company worth investing in." I don't agree. I assert that buybacks and growth initiatives are frequently executed poorly. Worse, they are frequently initiated in an attempt to shape market sentiment, partly in response to this "isn't worth investing in" philosophy. Furthermore, they are frequently funded with debt or, conversely, funded with excess cash on hand that management doesn't know what to do with. Buybacks are also frequently timed poorly (made when the company’s share price is overvalued) and/or initiated for short-term gain by company insiders (by inflating the value of stock options held by members of the company's executive team and upper-level management).

Closing

Dividend investing is a viable option for investing in the stock market, especially for early retirees, either in concert with total market indexing or instead of it. With that being said, I don't begrudge anyone who chooses total market indexing, exclusively. It is a very good option. Just as with most things in life, there are arguments for and against dividend investing. And whether or not you find dividend investing a compelling option will come down to your preferences and personal life/financial situation.

My own personal strategy is based on mirroring the holdings of a real-money Morningstar DividendInvestor portfolio. If you find this specific dividend investing strategy appealing, taking a closer look into it is easy. A 1-year subscription to Morningstar DividendInvestor includes a 30-day trial. A subscription also includes The Morningstar Guide to Dividend Investing, which is a good tutorial on dividend investing.

Are there any arguments for or against dividend investing that I've misrepresented - or left out entirely? Is dividend investing now on your radar as an option because of what I've written here? I'd love to hear your thoughts. Please leave a comment below.

Leave a comment

All comments are subject to review, so there will be a delay before they appear. You may include Markdown in your comment. I use the Akismet filtering service to reduce spam. Learn how Akismet processes comment data.2 comments

I also have been a subscriber of the Dividend Investor. I truly believe the quality of the newsletter suffered tremendously with the departure of Josh Peters. Unfortunately several of the stocks you listed above have had dividend cuts. So in addition to a loss of share price, the income generated from the portfolio has diminished. Additionally in the past dividend stocks weathered bear markets better than non-dividend stocks. Unfortunately this has not been the case this time. I've learned the hard way to focus on total return not just dividends. Just compare the twelve month's performance of Pfizer vs Lilly and tell me which you would have rather owned despite Lilly's smaller dividend.